Those who saw him hushed. On Church Street. Liberty. Cortlandt. West Street. Fulton. Vesey.

—Colum McCann, Let The Great World Spin

Despite having lived in New York City for most of the 2010s and worked in Lower Manhattan for a few of them, I still didn’t know where these streets were when I was reading Colum McCann’s novel at the end of 2019.

Knowing the names of a city’s streets has always been meaningful to me, despite its waning utility. But aside from being useful if the internet happens to be down or if one’s GPS is on the fritz, streets somehow make me feel connected to a city in a way that I find important. The denizens of a place have so little in common with one another aside from their shared geography, and it sometimes disappoints me that the simple act of asking for directions is a dwindling reason to have a conversation in the age of the smartphone. But at least it’s still a valid one.

At the same time that I was reading Let The Great World Spin, I had a desire to tinker with Aseprite, a pixel art program that had been recommended to me—but I also hadn’t done anything visually creative for years, and was terrified of a blank canvas.

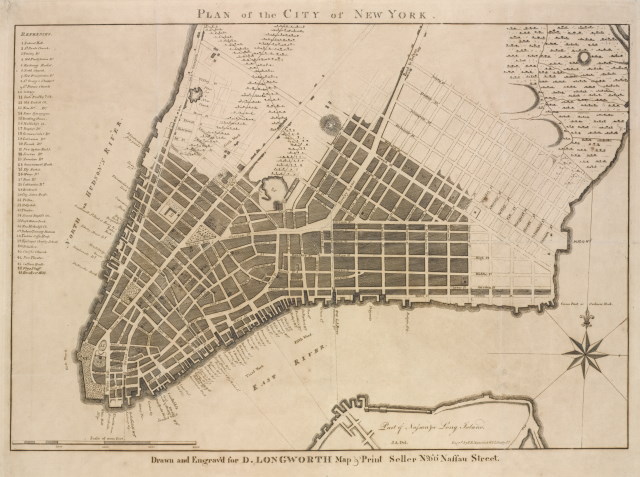

Soon I had somehow stumbled upon an amazing map of Manhattan from somewhere between 1790-1799 in the New York Public Library’s Digital Collection, and my mind was suddenly filled with possibilities.

What would it be like to have some kind of pixel-art adventure game set in eighteenth century New York City? Or a roguelike? Or a roguelike adventure game?

Eventually I decided that the least I could do would be to simply make a pixel art version of the map I had found: this would give me experience with Aseprite without much creative pressure, and the act of making a map of the city would help me become more familiar with its streets. Two birds, one stone.

Creating the map in Aseprite was satisfying: I could be creative without a fear of failure, like bumper bowling with art. I painted the roads in a way that would allow them to be navigated through WASD-key movement if I decided to make some kind of adventure game, and I cropped the canvas so that the present-day location of the JustFix.nyc office would be at the northeast corner.

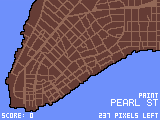

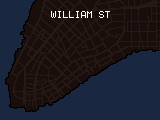

Soon I settled on a simple game of rote memorization: something that would prompt me with a street to “paint” on the screen with my mouse or finger, depending on what kind of device I was using, so that I could reinforce my knowledge of the city’s streets. A far cry from an adventure game, but it would be fun to make and useful to me, at least.

The only thing this lacked was a sense of narrative. Each street had a multitude of stories behind it; some of these I’d learned from walking tours like Slavery and Resistance in NYC by Mariame Kaba, some from historical fiction like Pete Hammill’s Forever. For others, I decided to do some research and learn about why these streets were called what they were. Soon I was consulting Wikipedia and had bought a book called Manhattan Street Names Past and Present by Dan Rogerson, and was knee-deep in the bowels of NYC history.

So, I added “street stories” to my nascent game: little blurbs that could fit in the 160x120 pixel screen I’d constrained myself to, written in a 3x5 pixel font I’d created that was not exactly the pinnacle of readability. But it was all mine and that was enough for now.

The result, Paint Manhattan Circa 1799, is something I’m reasonably proud of. A simple game, obstinately handcrafted, that helps me and possibly others become acquainted with the layout and history of a decent city.